Foot Core System

Published on

29 Dec 2017

Call us on: (03) 9975 4133

In a recent article in 2014, McKeon et al explore the evolution of our feet; the intrinsic and extrinsic stability of the foot; and incorporate this into assessment and treatment of the foot. Here is a summary of that article by Laura Hanson.

Foot Core System – Explained

Our feet are our foundations and subject to repetitive loads during every day activities and exercise, so it’s not surprising they can be subject to injury! This can either be through trauma such as broken bones or sprained ankles, (causing de-conditioning as a result of periods of reduced activity or immobilisation); or through repetitive load over a period of time.

The foot is very complex and is made up of many bones, joints, ligaments and muscles. It has varied functions, from providing support and stability at heel strike and push off, to being mobile and accommodating loads and uneven terrain during mid phase of gait.

The foot evolved as we became upright and started walking on two feet. It adapted for the purpose of running as well as walking through the presence of the Achilles tendon and other ligaments and tendons along the sole of the foot. These offer strong resistance to loads that occur during running and provide a ‘spring’ to absorb and release energy, which propels us forwards.

McKeon et al use Panjabi’s proposed system of stability, and apply it to the foot. This theory describes the relationship between –

- Active structures (muscles and tendons attaching to bones)

- Passive structures (bones, joints, and ligaments)

- Neural structures (sensory receptors in muscles, ligaments, tendons, and so on, that provide us with our ‘body awareness’)

Active system

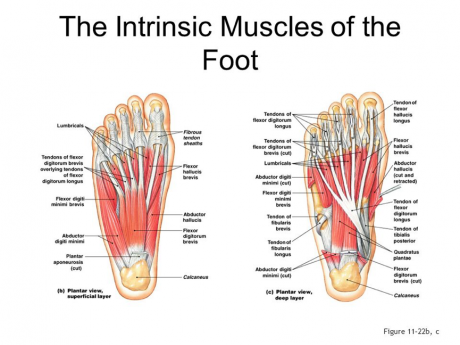

The active components of the foot include intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. Intrinsic muscles are the small, local muscles situated within the foot whereas the extrinsic muscles originate in the lower leg, cross the ankle, and insert into the foot.

The intrinsic muscles –

- support the arches of the foot

- are more active in dynamic tasks such as walking

- increase in activity as the demands of the task increase e.g. moving from standing on two feet to one

- work together as a unit

The extrinsic muscles generate foot and ankle movement via their long tendons. They also influence passive structures. For example, the Achilles tendon from the calf muscle group influences tension in the plantar fascia via a common connection at the heel. When the calf tightens so does the plantar fascia, which assists the foot at push off.

Passive system

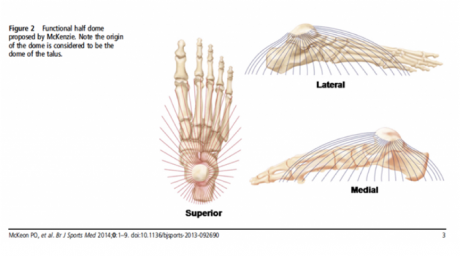

The arrangement of the bones and ligaments of the foot form four arches: the medial and lateral longitudinal arches; and the anterior and posterior transverse metatarsal arches. Essentially these can be viewed as ‘a dome’.

This dome is supported by the plantar fascia and other ligaments, as well as from local muscle support of the intrinsic muscles, and indirectly by the extrinsic muscles.

Neural system

Sensory receptors within the plantar fascia, ligaments, muscles, etc. are essential for balance and gait. When the intrinsic muscles are stretched through changes to the foot dome posture, they provide immediate sensory feedback. The receptors within the muscles can be trained to increase their sensitivity to changes in foot posture. Just as the ‘core muscles’ of the spine and pelvis play an important role in relation to feedback about spinal posture, the intrinsic foot muscles are important to provide feedback on foot posture.

Clinical assessment and treatment

McKeon et al highlight that there has been little attention paid to the clinical assessment of the foot intrinsic muscles in research. They emphasise that this is an area where further research is needed, as has been done with the deep postural muscles of the trunk. Being able to assess the foot core system gives us an understanding of how the foot is able to cope with loads during activity.

Traditionally, therapeutic exercises for the foot involve the global muscles over the intrinsic muscles. The current approach is to teach ‘doming’ exercises or ‘foot shortening’ exercises whereby the foot ‘shortened’ by drawing the first toe joint towards the heel, thereby increasing the ‘dome’ of the foot.

As has been done with spinal control exercises, McKeon et al advocate building control of the intrinsic muscles first before gradually increasing load, taking care not to activate any global muscles until appropriate. For instance, these exercises should be taught and practised in sitting first before progressing to standing, then standing on one leg, and lastly during functional activities such as squats and hops.

There is increasing evidence that this form of exercise is effective. Early evidence suggests that patients with chronic ankle instability improved their function better during balance exercises compared with a group that did not perform foot doming during balance exercises.

We’re Here to Help

if you experience foot or ankle pain, book an appointment to speak to one of our physiotherapists about starting a foot doming program!